Second law of thermodynamics

| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

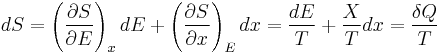

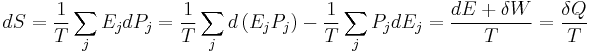

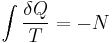

The second law of thermodynamics is an expression of the universal principle of decay observable in nature. It is measured and expressed in terms of a property called entropy, stating that the entropy of an isolated system which is not in equilibrium will tend to increase over time, approaching a maximum value at equilibrium; and that the entropy change dS of a system undergoing any infinitesimal reversible process is given by  , where

, where  is the heat supplied to the system and T is the absolute temperature of the system. In classical thermodynamics, the second law is a basic postulate applicable to any system involving measurable heat energy transfer, while in statistical thermodynamics, the second law is a consequence of the assumed randomness of molecular chaos, see fundamental postulate.

is the heat supplied to the system and T is the absolute temperature of the system. In classical thermodynamics, the second law is a basic postulate applicable to any system involving measurable heat energy transfer, while in statistical thermodynamics, the second law is a consequence of the assumed randomness of molecular chaos, see fundamental postulate.

The origin of the second law can be traced to French physicist Sadi Carnot's 1824 paper Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, which presented the view that motive power (work) is due to the flow of caloric (heat) from a hot to cold body (working substance). In simple terms, the second law is an expression of the fact that over time, differences in temperature, pressure, and chemical potential tend to even out in a physical system that is isolated from the outside world. Entropy is a measure of how much this evening-out process has progressed.

There are many versions of the second law, but they all have the same effect, which is to explain the phenomenon of irreversibility in nature.

Contents |

Introduction

Versions of the Law

There are many ways of stating the second law of thermodynamics, but all are equivalent in the sense that each form of the second law logically implies every other form.[1] Thus, the theorems of thermodynamics can be proved using any form of the second law and third law.

The formulation of the second law that refers to entropy directly is as follows:

In a system, a process that occurs will tend to increase the total entropy of the universe.

Thus, while a system can go through some physical process that decreases its own entropy, the entropy of the universe (which includes the system and its surroundings) must increase overall. (An exception to this rule is a reversible or "isentropic" process, such as frictionless adiabatic compression.) Processes that decrease the total entropy of the universe are impossible. If a system is at equilibrium, by definition no spontaneous processes occur, and therefore the system is at maximum entropy.

A second formulation, due to Rudolf Clausius, is the simplest formulation of the second law, the heat formulation or Clausius statement:

Heat generally cannot flow spontaneously from a material at lower temperature to a material at higher temperature.

Informally, "Heat doesn't flow from cold to hot (without work input)", which is true obviously from ordinary experience. For example in a refrigerator, heat flows from cold to hot, but only when aided by an external agent (i.e. the compressor). Note that from the mathematical definition of entropy, a process in which heat flows from cold to hot has decreasing entropy. This can happen in a non-isolated system if entropy is created elsewhere, such that the total entropy is constant or increasing, as required by the second law. For example, the electrical energy going into a refrigerator is converted to heat and goes out the back, representing a net increase in entropy.

The exception to this is for statistically unlikely events where hot particles will "steal" the energy of cold particles enough that the cold side gets colder and the hot side gets hotter, for an instant. Such events have been observed at a small enough scale where the likelihood of such a thing happening is significant.[2] The mathematics involved in such an event are described by fluctuation theorem.

A third formulation of the second law, by Lord Kelvin, is the heat engine formulation, or Kelvin statement:

It is impossible to convert heat completely into work in a cyclic process.

That is, it is impossible to extract energy by heat from a high-temperature energy source and then convert all of the energy into work. At least some of the energy must be passed on to heat a low-temperature energy sink. Thus, a heat engine with 100% efficiency is thermodynamically impossible. This also means that it is impossible to build solar panels that generate electricity solely from the infrared band of the electromagnetic spectrum without consideration of the temperature on the other side of the panel (as is the case with conventional solar panels that operate in the visible spectrum).

A fourth version of the second law was deduced by the Greek mathematician Constantin Carathéodory. The Carathéodory statement:

In the neighbourhood of any equilibrium state of a thermodynamic system, there are equilibrium states that are adiabatically inaccessible.

Formulations of the second law in modern textbooks that introduce entropy from the statistical point of view, often contain two parts. The first part states that the entropy of an isolated system cannot decrease, or, to be more precise, the probability of an entropy decrease is exceedingly small. The second part gives the relation between infinitesimal entropy increase of a system and an infinitesimal amount of absorbed heat in case of an arbitrary infinitesimal reversible process:  . The reason why these two statements are not combined into a single statement is because the first part refers to a general non-equilibrium process in which temperature is not defined.

. The reason why these two statements are not combined into a single statement is because the first part refers to a general non-equilibrium process in which temperature is not defined.

Microscopic systems

Thermodynamics is a theory of macroscopic systems and as such all its mathematical expressions including the Clausius expression for entropy applies only to systems with well-defined temperatures. The second law however 'knows' no such boundary and the Clausius expression turns out to be just a special case of the more general Boltzman equation, see statistical mechanics. The Boltzman equation reveals the true basis of the second law as the probability that any particular state may exist and the tendency for any system to move toward its most probable state. This raises the question "What is the minimum mass for which we may say the second law applies?". For example, in a system of two molecules, there is a non-trivial probability that the slower-moving ("cold") molecule transfers energy to the faster-moving ("hot") molecule. Such tiny systems are not part of classical thermodynamics, but they can be investigated by quantum thermodynamics by using statistical mechanics. For any isolated system with a mass of more than a few picograms, probabilities of observing a decrease in entropy approach zero.[3]

Energy dispersal

The second law of thermodynamics is an axiom of thermodynamics concerning heat, entropy, and the direction in which thermodynamic processes can occur. For example, the second law implies that heat does not flow spontaneously from a cold material to a hot material, but it allows heat to flow from a hot material to a cold material. Roughly speaking, the second law says that in an isolated system, concentrated energy disperses over time, and consequently less concentrated energy is available to do useful work. Energy dispersal also means that differences in temperature, pressure, and density even out. Again roughly speaking, thermodynamic entropy is a measure of energy dispersal, and so the second law is closely connected with the concept of entropy.

Broader applications

The second law of thermodynamics has been proven mathematically for thermodynamic systems, where entropy is defined in terms of heat divided by the absolute temperature. The second law is often applied to other situations, such as black hole thermodynamics, and the complexity of life, or orderliness. [4] However it is incorrect to apply the closed-system expression of the second law of thermodynamics to any one sub-system connected by mass-energy flows to another ("open system"). In sciences such as biology and biochemistry the application of thermodynamics is well-established, e.g. biological thermodynamics. The general viewpoint on this subject is summarized well by biological thermodynamicist Donald Haynie; as he states: "Any theory claiming to describe how organisms originate and continue to exist by natural causes must be compatible with the first and second laws of thermodynamics."[5]

Furthermore, the second law is only true of closed systems. It is easy to decrease entropy, with an energy source. For example, a refrigerator separates warm and cold air, but only when it is plugged in. Since all biology requires an external energy source, there's nothing unusual (thermodynamically) with it growing more complex with time.

Overview

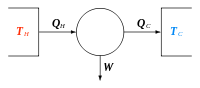

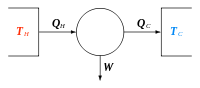

In a general sense, the second law is that temperature differences between systems in contact with each other tend to equalize and that work can be obtained from these non-equilibrium differences, but that loss of heat occurs, in the form of entropy, when work is done.[6] Pressure differences, density differences, and particularly temperature differences, all tend to equalize if given the opportunity. This means that an isolated system will eventually have a uniform temperature. A heat engine is a mechanical device that provides useful work from the difference in temperature of two bodies:

During the 19th century, the second law was synthesized, essentially, by studying the dynamics of the Carnot heat engine in coordination with James Joule's mechanical equivalent of heat experiments. Since any thermodynamic engine requires such a temperature difference, it follows that useful work cannot be derived from an isolated system in equilibrium; there must always be an external energy source and a cold sink. By definition, perpetual motion machines of the second kind would have to violate the second law to function.

History

The first theory of the conversion of heat into mechanical work is due to Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824. He was the first to realize correctly that the efficiency of this conversion depends on the difference of temperature between an engine and its environment.

Recognizing the significance of James Prescott Joule's work on the conservation of energy, Rudolf Clausius was the first to formulate the second law during 1850, in this form: heat does not flow spontaneously from cold to hot bodies. While common knowledge now, this was contrary to the caloric theory of heat popular at the time, which considered heat as a fluid. From there he was able to infer the principle of Sadi Carnot and the definition of entropy (1865).

Established during the 19th century, the Kelvin-Planck statement of the Second Law says, "It is impossible for any device that operates on a cycle to receive heat from a single reservoir and produce a net amount of work." This was shown to be equivalent to the statement of Clausius.

The ergodic hypothesis is also important for the Boltzmann approach. It says that, over long periods of time, the time spent in some region of the phase space of microstates with the same energy is proportional to the volume of this region, i.e. that all accessible microstates are equally probable over long period of time. Equivalently, it says that time average and average over the statistical ensemble are the same.

It has been shown that not only classical systems but also quantum mechanical ones tend to maximize their entropy over time. Thus the second law follows, given initial conditions with low entropy. More precisely, it has been shown that the local von Neumann entropy is at its maximum value with an extremely great probability.[7] The result is valid for a large class of isolated quantum systems (e.g. a gas in a container). While the full system is pure and therefore does not have any entropy, the entanglement between gas and container gives rise to an increase of the local entropy of the gas. This result is one of the most important achievements of quantum thermodynamics.

Today, much effort in the field is to understand why the initial conditions early in the universe were those of low entropy[8][9], as this is seen as the origin of the second law (see below).

Informal descriptions

The second law can be stated in various succinct ways, including:

- It is impossible to produce work in the surroundings using a cyclic process connected to a single heat reservoir (Kelvin, 1851).

- It is impossible to carry out a cyclic process using an engine connected to two heat reservoirs that will have as its only effect the transfer of a quantity of heat from the low-temperature reservoir to the high-temperature reservoir (Clausius, 1854).

- If thermodynamic work is to be done at a finite rate, free energy must be expended.[10]

Mathematical descriptions

In 1856, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius stated what he called the "second fundamental theorem in the mechanical theory of heat" in the following form:[11]

where Q is heat, T is temperature and N is the "equivalence-value" of all uncompensated transformations involved in a cyclical process. Later, in 1865, Clausius would come to define "equivalence-value" as entropy. On the heels of this definition, that same year, the most famous version of the second law was read in a presentation at the Philosophical Society of Zurich on April 24, in which, in the end of his presentation, Clausius concludes:

The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.

This statement is the best-known phrasing of the second law. Moreover, owing to the general broadness of the terminology used here, e.g. universe, as well as lack of specific conditions, e.g. open, closed, or isolated, to which this statement applies, many people take this simple statement to mean that the second law of thermodynamics applies virtually to every subject imaginable. This, of course, is not true; this statement is only a simplified version of a more complex description.

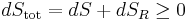

In terms of time variation, the mathematical statement of the second law for an isolated system undergoing an arbitrary transformation is:

where

- S is the entropy and

- t is time.

Statistical mechanics gives an explanation for the second law by postulating that a material is composed of atoms and molecules which are in constant motion. A particular set of positions and velocities for each particle in the system is called a microstate of the system and because of the constant motion, the system is constantly changing its microstate. Statistical mechanics postulates that, in equilibrium, each microstate that the system might be in is equally likely to occur, and when this assumption is made, it leads directly to the conclusion that the second law must hold in a statistical sense. That is, the second law will hold on average, with a statistical variation on the order of 1/√N where N is the number of particles in the system. For everyday (macroscopic) situations, the probability that the second law will be violated is practically zero. However, for systems with a small number of particles, thermodynamic parameters, including the entropy, may show significant statistical deviations from that predicted by the second law. Classical thermodynamic theory does not deal with these statistical variations.

Available useful work

An important and revealing idealized special case is to consider applying the Second Law to the scenario of an isolated system (called the total system or universe), made up of two parts: a sub-system of interest, and the sub-system's surroundings. These surroundings are imagined to be so large that they can be considered as an unlimited heat reservoir at temperature TR and pressure PR — so that no matter how much heat is transferred to (or from) the sub-system, the temperature of the surroundings will remain TR; and no matter how much the volume of the sub-system expands (or contracts), the pressure of the surroundings will remain PR.

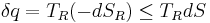

Whatever changes to dS and dSR occur in the entropies of the sub-system and the surroundings individually, according to the Second Law the entropy Stot of the isolated total system must not decrease:

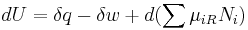

According to the First Law of Thermodynamics, the change dU in the internal energy of the sub-system is the sum of the heat δq added to the sub-system, less any work δw done by the sub-system, plus any net chemical energy entering the sub-system d ∑μiRNi, so that:

where μiR are the chemical potentials of chemical species in the external surroundings.

Now the heat leaving the reservoir and entering the sub-system is

where we have first used the definition of entropy in classical thermodynamics (alternatively, in statistical thermodynamics, the relation between entropy change, temperature and absorbed heat can be derived); and then the Second Law inequality from above.

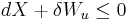

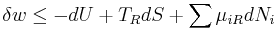

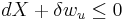

It therefore follows that any net work δw done by the sub-system must obey

It is useful to separate the work δw done by the subsystem into the useful work δwu that can be done by the sub-system, over and beyond the work pR dV done merely by the sub-system expanding against the surrounding external pressure, giving the following relation for the useful work that can be done:

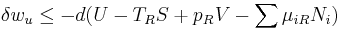

It is convenient to define the right-hand-side as the exact derivative of a thermodynamic potential, called the availability or exergy X of the subsystem,

The Second Law therefore implies that for any process which can be considered as divided simply into a subsystem, and an unlimited temperature and pressure reservoir with which it is in contact,

i.e. the change in the subsystem's exergy plus the useful work done by the subsystem (or, the change in the subsystem's exergy less any work, additional to that done by the pressure reservoir, done on the system) must be less than or equal to zero.

Special cases: Gibbs and Helmholtz free energies

When no useful work is being extracted from the sub-system, it follows that

with the exergy X reaching a minimum at equilibrium, when dX=0.

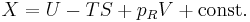

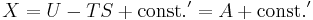

If no chemical species can enter or leave the sub-system, then the term ∑ μiR Ni can be ignored. If furthermore the temperature of the sub-system is such that T is always equal to TR, then this gives:

If the volume V is constrained to be constant, then

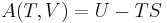

where A is the thermodynamic potential called Helmholtz free energy, A=U−TS. Under constant-volume conditions therefore, dA ≤ 0 if a process is to go forward; and dA=0 is the condition for equilibrium.

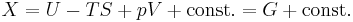

Alternatively, if the sub-system pressure p is constrained to be equal to the external reservoir pressure pR, then

where G is the Gibbs free energy, G=U−TS+PV. Therefore under constant-pressure conditions, if dG ≤ 0, then the process can occur spontaneously, because the change in system energy exceeds the energy lost to entropy. dG=0 is the condition for equilibrium. This is also commonly written in terms of enthalpy, where H=U+PV.

Application

In sum, if a proper infinite-reservoir-like reference state is chosen as the system surroundings in the real world, then the Second Law predicts a decrease in X for an irreversible process and no change for a reversible process.

is equivalent to

is equivalent to

This expression together with the associated reference state permits a design engineer working at the macroscopic scale (above the thermodynamic limit) to utilize the Second Law without directly measuring or considering entropy change in a total isolated system. (Also, see process engineer). Those changes have already been considered by the assumption that the system under consideration can reach equilibrium with the reference state without altering the reference state. An efficiency for a process or collection of processes that compares it to the reversible ideal may also be found (See second law efficiency.)

This approach to the Second Law is widely utilized in engineering practice, environmental accounting, systems ecology, and other disciplines.

Proof of the Second Law

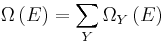

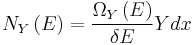

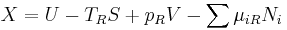

As mentioned above, in statistical mechanics, the Second Law is not a postulate, rather it is a consequence of the fundamental postulate, also known as the equal prior probability postulate, so long as one is clear that simple probability arguments are applied only to the future, while for the past there are auxiliary sources of information which tell us that it was low entropy. The first part of the second law, which states that the entropy of a thermally isolated system can only increase is a trivial consequence of the equal prior probability postulate, if we restrict the notion of the entropy to systems in thermal equilibrium. The entropy of an isolated system in thermal equilibrium containing an amount of energy of  is:

is:

where  is the number of quantum states in a small interval between

is the number of quantum states in a small interval between  and

and  . Here

. Here  is a macroscopically small energy interval that is kept fixed. Strictly speaking this means that the entropy depends on the choice of

is a macroscopically small energy interval that is kept fixed. Strictly speaking this means that the entropy depends on the choice of  . However, in the thermodynamic limit (i.e. in the limit of infinitely large system size), the specific entropy (entropy per unit volume or per unit mass) does not depend on

. However, in the thermodynamic limit (i.e. in the limit of infinitely large system size), the specific entropy (entropy per unit volume or per unit mass) does not depend on  .

.

Suppose we have an isolated system whose macroscopic state is specified by a number of variables. These macroscopic variable can e.g. refer to the total volume, the positions of pistons in the system etc.. Then  will depend on the values of these variables. If a variable is not fixed, e.g. we do not clamp a piston in a certain position, then because all the accessible states are equally likely in equilibrium, the free variable in equilibrium will be such that

will depend on the values of these variables. If a variable is not fixed, e.g. we do not clamp a piston in a certain position, then because all the accessible states are equally likely in equilibrium, the free variable in equilibrium will be such that  is maximized as that is the most probable situation in equilibrium.

is maximized as that is the most probable situation in equilibrium.

If the variable was initially fixed to some value then upon release and when the new equilibrium has been reached, the fact the variable will adjust itself so that  is maximized, implies that that the entropy will have increased or it will have stayed the same (if the value at which the variable was fixed happened to be the equilibrium value).

is maximized, implies that that the entropy will have increased or it will have stayed the same (if the value at which the variable was fixed happened to be the equilibrium value).

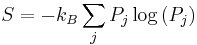

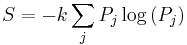

The entropy of a system that is not in equilibrium can be defined as:

see here. Here the  are the probabilities for the system to be found in the states labeled by the subscript j. In thermal equilibrium the probabilities for states inside the energy interval

are the probabilities for the system to be found in the states labeled by the subscript j. In thermal equilibrium the probabilities for states inside the energy interval  are all equal to

are all equal to  , and in that case the general definition coincides with the previous definition of S that applies to the case of thermal equilibrium.

, and in that case the general definition coincides with the previous definition of S that applies to the case of thermal equilibrium.

Suppose we start from an equilibrium situation and we suddenly remove a constraint on a variable. Then right after we do this, there are a number  of accessible microstates, but equilibrium has not yet been reached, so the actual probabilities of the system being in some accessible state are not yet equal to the prior probability of

of accessible microstates, but equilibrium has not yet been reached, so the actual probabilities of the system being in some accessible state are not yet equal to the prior probability of  . We have already seen that in the final equilibrium state, the entropy will have increased or have stayed the same relative to the previous equilibrium state. Boltzmann's H-theorem, however, proves that the entropy will increase continuously as a function of time during the intermediate out of equilibrium state.

. We have already seen that in the final equilibrium state, the entropy will have increased or have stayed the same relative to the previous equilibrium state. Boltzmann's H-theorem, however, proves that the entropy will increase continuously as a function of time during the intermediate out of equilibrium state.

Proof of  for reversible processes

for reversible processes

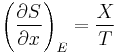

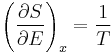

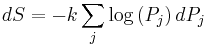

The second part of the Second Law states that the entropy change of a system undergoing a reversible process is given by:

where the temperature is defined as:

![\frac{1}{k T}\equiv\beta\equiv\frac{d\log\left[\Omega\left(E\right)\right]}{dE}\,](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/8b77282aaf38833c81c764e85b369215.png)

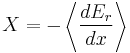

See here for the justification for this definition. Suppose that the system has some external parameter, x, that can be changed. In general, the energy eigenstates of the system will depend on x. According to the adiabatic theorem of quantum mechanics, in the limit of an infinitely slow change of the system's Hamiltonian, the system will stay in the same energy eigenstate and thus change its energy according to the change in energy of the energy eigenstate it is in.

The generalized force, X, corresponding to the external variable x is defined such that  is the work performed by the system if x is increased by an amount dx. E.g., if x is the volume, then X is the pressure. The generalized force for a system known to be in energy eigenstate

is the work performed by the system if x is increased by an amount dx. E.g., if x is the volume, then X is the pressure. The generalized force for a system known to be in energy eigenstate  is given by:

is given by:

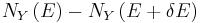

Since the system can be in any energy eigenstate within an interval of  , we define the generalized force for the system as the expectation value of the above expression:

, we define the generalized force for the system as the expectation value of the above expression:

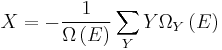

To evaluate the average, we partition the  energy eigenstates by counting how many of them have a value for

energy eigenstates by counting how many of them have a value for  within a range between

within a range between  and

and  . Calling this number

. Calling this number  , we have:

, we have:

The average defining the generalized force can now be written:

We can relate this to the derivative of the entropy w.r.t. x at constant energy E as follows. Suppose we change x to x + dx. Then  will change because the energy eigenstates depend on x, causing energy eigenstates to move into or out of the range between

will change because the energy eigenstates depend on x, causing energy eigenstates to move into or out of the range between  and

and  . Let's focus again on the energy eigenstates for which

. Let's focus again on the energy eigenstates for which  lies within the range between

lies within the range between  and

and  . Since these energy eigenstates increase in energy by Y dx, all such energy eigenstates that are in the interval ranging from E - Y dx to E move from below E to above E. There are

. Since these energy eigenstates increase in energy by Y dx, all such energy eigenstates that are in the interval ranging from E - Y dx to E move from below E to above E. There are

such energy eigenstates. If  , all these energy eigenstates will move into the range between

, all these energy eigenstates will move into the range between  and

and  and contribute to an increase in

and contribute to an increase in  . The number of energy eigenstates that move from below

. The number of energy eigenstates that move from below  to above

to above  is, of course, given by

is, of course, given by  . The difference

. The difference

is thus the net contribution to the increase in  . Note that if Y dx is larger than

. Note that if Y dx is larger than  there will be the energy eigenstates that move from below E to above

there will be the energy eigenstates that move from below E to above  . They are counted in both

. They are counted in both  and

and  , therefore the above expression is also valid in that case.

, therefore the above expression is also valid in that case.

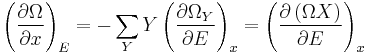

Expressing the above expression as a derivative w.r.t. E and summing over Y yields the expression:

The logarithmic derivative of  w.r.t. x is thus given by:

w.r.t. x is thus given by:

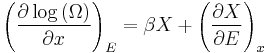

The first term is intensive, i.e. it does not scale with system size. In contrast, the last term scales as the inverse system size and will thus vanishes in the thermodynamic limit. We have thus found that:

Combining this with

Gives:

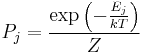

Proof for systems described by the canonical ensemble

If a system is in thermal contact with a heat bath at some temperature T then, in equilibrium, the probability distribution over the energy eigenvalues are given by the canonical ensemble:

Here Z is a factor that normalizes the sum of all the probabilities to 1, this function is known as the partition function. We now consider an infintesimal reversible change in the temperature and in the external parameters on which the energy levels depend. It follows from the general formula for the entropy:

that

Inserting the formula for  for the canonical ensemble in here gives:

for the canonical ensemble in here gives:

Criticisms

Owing to the somewhat ambiguous nature of the formulation of the second law, i.e. the postulate that the quantity heat divided by temperature increases in spontaneous natural processes, it has occasionally been subject to criticism as well as attempts to dispute or disprove it. Clausius himself even noted the abstract nature of the second law. In his 1862 memoir, for example, after mathematically stating the second law by saying that integral of the differential of a quantity of heat divided by temperature must be less than or equal to zero for every cyclical process which is in any way possible:[11] (Clausius Inequality)

,

,

Clausius then stated:

Although the necessity of this theorem admits of strict mathematical proof if we start from the fundamental proposition above quoted it thereby nevertheless retains an abstract form, in which it is with difficulty embraced by the mind, and we feel compelled to seek for the precise physical cause, of which this theorem is a consequence.

Recall that heat and temperature are statistical, macroscopic quantities that become somewhat ambiguous when dealing with a small number of atoms.

Non-isolated systems

Generally, the second law is said to apply only to isolated systems. However, it has been asserted that the second law also applies to non-isolated, or open systems. According to Arnold Sommerfeld:[12]

The quantity of entropy generated locally cannot be negative irrespective of whether the system is isolated or not.

Also, John Ross writes:[13]

Ordinarily the second law is stated for isolated systems, but the second law applies equally well to open systems.

Perpetual motion of the second kind

Before 1850, heat was regarded as an indestructible particle of matter. This was called the “material hypothesis”, as based principally on the purported[14][15][16][17] views of Sir Isaac Newton. It was on these views, partially, that in 1824 Sadi Carnot formulated the initial version of the second law. It soon was realized, however, that if the heat particle was conserved, and as such not changed in the cycle of an engine, that it would be possible to send the heat particle cyclically through the working fluid of the engine and use it to push the piston and then return the particle, unchanged, to its original state. In this manner perpetual motion could be created and used as an unlimited energy source. Thus, historically, people have always been attempting to create a perpetual motion machine, in violation of the second law, in the hope of solving the world's energy limitations.

Maxwell's Demon

In 1871, James Clerk Maxwell proposed a thought experiment, now called Maxwell's demon, which challenged the second law. This experiment reveals that the information theoretical definition of entropy is more fundamental than the definition according to classical thermodynamics.

Time's arrow and the origin of the second law

The second law is a law about macroscopic irreversibility, and so may appear to violate the principle of T-symmetry. Boltzmann first investigated the link with microscopic reversibility. In his H-theorem he gave an explanation, by means of statistical mechanics, for dilute gases in the zero density limit where the ideal gas equation of state holds. He derived the second law of thermodynamics not from mechanics alone, but also from the probability arguments. His idea was to write an equation of motion for the probability that a single particle has a particular position and momentum at a particular time. One of the terms in this equation accounts for how the single particle distribution changes through collisions of pairs of particles. This rate depends on the probability of pairs of particles. Boltzmann introduced the assumption of molecular chaos to reduce this pair probability to a product of single particle probabilities. From the resulting Boltzmann equation he derived his famous H-theorem, which implies that on average the entropy of an ideal gas can only increase.

The assumption of molecular chaos in fact violates time reversal symmetry. It assumes that particle momenta are uncorrelated before collisions. If you replace this assumption with "anti-molecular chaos," namely that particle momenta are uncorrelated after collision, then you can derive an anti-Boltzmann equation and an anti-H-Theorem which implies entropy decreases on average. Thus we see that in reality Boltzmann did not succeed in solving Loschmidt's paradox. The molecular chaos assumption is the key element that introduces the arrow of time.

The origin of the arrow of time is today usually thought to be the smooth, uncorrelated (and hence low entropy) initial conditions that existed in the very early universe.[18][19][20][21]

Complex systems in Creationist arguments

It is occasionally claimed that the second law is incompatible with autonomous self-organisation, or even the coming into existence of complex systems. This is a common creationist argument against evolution.[22]

In sciences such as biology and biochemistry the application of thermodynamics is well-established, e.g. biological thermodynamics. The general viewpoint on this subject is summarized well by biological thermodynamicist Donald Haynie; as he states:

| “ | Any theory claiming to describe how organisms originate and continue to exist by natural causes must be compatible with the first and second laws of thermodynamics.[23] | ” |

This is very different, however, from the claim made by many creationists that evolution violates the second law of thermodynamics. Evidence indicates that biological systems and evolution of those systems conform to the second law, since although biological systems may become more ordered, the net change in entropy for the entire universe is still positive as a result of evolution.[24] Additionally, the process of natural selection responsible for such local increase in order may be mathematically derived from the expression of the second law equation for non-equilibrium connected open systems,[25] arguably making the Theory of Evolution itself an expression of the Second Law.

It is incorrect to apply the closed-system expression of the second law of thermodynamics to any one sub-system connected by mass-energy flows to another ("open system"); the second law is only true of closed systems. It is easy to decrease entropy with an energy source (such as the sun). For example, a refrigerator separates warm and cold air, but only when it is plugged in. Since all biology requires an external energy source, there's nothing unusual (thermodynamically) with it growing more complex with time. In fact, as hot systems cool down in accordance with the second law, it is not unusual for them to undergo spontaneous symmetry breaking, i.e. for structure to spontaneously appear as the temperature drops below a critical threshold. Complex structures, such as Bénard cells, also spontaneously appear where there is a steady flow of energy from a high temperature input source to a low temperature external sink.

Furthermore, a system may decrease its local entropy provided the resulting increase of the entropy to its surrounding is greater than or equal to the local decrease. A good example of this is crystallization. As a liquid cools, crystals begin to form inside it. While these crystals are more ordered than the liquid they originated from, in order for them to form they must release a great deal of heat, known as the latent heat of fusion. This heat flows out of the system and increases the entropy of its surroundings to a greater extent than the decrease of energy that the liquid underwent in the formation of crystals.

Quotes

"The law that entropy always increases holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation." — Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

The tendency for entropy to increase in isolated systems is expressed in the second law of thermodynamics — perhaps the most pessimistic and amoral formulation in all human thought. — Gregory Hill and Kerry Thornley, Principia Discordia (1965)

There are almost as many formulations of the second law as there have been discussions of it. — Philosopher / Physicist P.W. Bridgman, (1941)

See also

|

|

- Second-law efficiency

- Relativistic heat conduction

References

- ↑ Fermi, Enrico (1956) [1936]. Thermodynamics. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-60361-X.

- ↑ G.M. Wang, E.M. Sevick, E. Mittag, D.J. Searles & Denis J. Evans (2002). "Experimental demonstration of violations of the Second Law of Thermodynamics for small systems and short time scales". Physical Review Letters 89: 050601/1–050601/4. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.050601

- ↑ Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. (1996). Statistical Physics Part 1. Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3372-7.

- ↑ Hammes, Gordon, G. (2000). Thermodynamics and Kinetics for the Biological Sciences. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-37491-1.

- ↑ Haynie, Donald, T. (2001). Biological Thermodynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79549-4.

- ↑ Mendoza, E. (1988). Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire – and other Papers on the Second Law of Thermodynamics by E. Clapeyron and R. Clausius. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-44641-7.

- ↑ Gemmer, Jochen; Otte, Alexander; Mahler, Günter (2001). "Quantum Approach to a Derivation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics". Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 (10): 1927–1930. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1927. PMID 11289822. http://prola.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v86/i10/p1927_1

- ↑ Does Inflation Provide Natural Initial Conditions for the Universe?, Carrol SM, Chen J, Gen.Rel.Grav. 37 (2005) 1671-1674; Int.J.Mod.Phys. D14 (2005) 2335-2340, arXiv:gr-qc/0505037v1

- ↑ The arrow of time and the initial conditions of the universe, Wald RM, Studies In History and Philosophy of Science Part B, Volume 37, Issue 3, September 2006, Pages 394-398

- ↑ Stoner, C.D. (2000). Inquiries into the Nature of Free Energy and Entropy – in Biochemical Thermodynamics. Entropy, Vol 2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Clausius, R. (1865). The Mechanical Theory of Heat – with its Applications to the Steam Engine and to Physical Properties of Bodies. London: John van Voorst, 1 Paternoster Row. MDCCCLXVII.

- ↑ Sommerfeld, Arnold (1956). Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics. New York: Academic Press. p. 155.

- ↑ Ross, John (7 July 1980). "Letter to the Editor". Chemical and Engineering News: 40.

- ↑ Wikipedia: Newton's views as 'Whig history' (near end of section)

- ↑ Newton hated the perpetual motion controversy

- ↑ "Newton's Cradle" (toy)

- ↑ "The seekers after perpetual motion are trying to get something from nothing.", Sir Isaac Newton

- ↑ The Thermodynamic Arrow: Puzzles and Pseudo-Puzzles, Price H., Proceedings of Time and Matter, Venice, 2002

- ↑ Halliwell, J.J. et al. (1994). Physical Origins of Time Asymmetry. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-56837-4.

- ↑ Arrow of time in cosmology, Hawking S.W., Phys. Rev. D 32, 2489 - 2495 (1985)

- ↑ scholarpedia: Time's arrow and Boltzmann's entropy

- ↑ Rennie, John (2002). "15 Answers to Creationist Nonsense". Scientific American 287 (1): 78–85. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=000D4FEC-7D5B-1D07-8E49809EC588EEDF page 82, accessed 2007-09-10

- ↑ Haynie, Donald, T. (2001). Biological Thermodynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79549-4.

- ↑ Five Major Misconceptions about Evolution

- ↑ Ville R. I. Kaila and Arto Annila (2008). "Natural selection for least action". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 464: 3055. doi:10.1098/rspa.2008.0178.

Further reading

- Goldstein, Martin, and Inge F., 1993. The Refrigerator and the Universe. Harvard Univ. Press. Chpts. 4-9 contain an introduction to the Second Law, one a bit less technical than this entry. ISBN 978-0-674-75324-2

- Leff, Harvey S., and Rex, Andrew F. (eds.) 2003. Maxwell's Demon 2 : Entropy, classical and quantum information, computing. Bristol UK; Philadelphia PA: Institute of Physics. ISBN 978-0-585-49237-7

- Halliwell, J.J. et al. (1994). Physical Origins of Time Asymmetry. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-56837-4. (technical).

- Iftime, M.D.(2010). Hidden complexity in the properties of far-fields arXiv preprint

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Philosophy of Statistical Mechanics" -- by Lawrence Sklar.

- Second law of thermodynamics in the MIT Course Unified Thermodinamics and Propulsion from Prof. Z. S. Spakovszky

- E.T. Jaynes, 1988, "The evolution of Carnot's principle," in G. J. Erickson and C. R. Smith (eds.) Maximum-Entropy and Bayesian Methods in Science and Engineering, Vol 1, p. 267.

- Website devoted to the Second Law.

![S = k \log\left[\Omega\left(E\right)\right]\,](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/c04285070a2bf9a8397a5d9e90b6076c.png)